Imagine the very earliest artist at work, sitting on the shore of some rugged coastline, using a sharp rock to etch pleasing patterns into a shell. The first humans to create art used natural dyes found in plants and minerals, wove patterns in natural fibers, and carved images on all kinds of materials. Our creative drive emerged over and over again across the globe. Some of the oldest art on record is found in caves, where the artwork was protected from the elements for millennia. Recent evidence suggests some of the earliest works of art are about 44,000 years old!

Through time, the tools used by artists have naturally evolved along with our culture and our capabilities. In the information age, artists now have access to an explosion of new creative tools to play with. In fact, on the extreme end of this trend, humans have now created technology that is creating its own art. For several years, art created by artificial intelligence has hit the art scene, with all the controversy one would expect.

I’ve been thinking about this for quite a while in regard to my own art. Over the last 30 years, I’ve created dozens of works of digital art. Within the last couple of years I’ve begun to include digital art in my portfolio of fine art, with a place among more traditional tools.

What I notice is, the response from art appreciators varies quite a bit. Most, upon finding out the work was created using digital tools, are surprised, intrigued or curious. For others, I sense a reservation, as though artwork created using traditional methods is “real” and the use of technology is a kind of shortcut, or automated process.

My personal take? I believe art is not tied to a particular technology or means, nor even to what a human can create. The human mind is immensely capable of appreciating art: we respond emotionally and intellectually to what we experience. But whether we respond to something created by another human, by nature, or by our own technology is a blurry line. Especially when considering that the vast majority of humanity’s artistic past involves mimicking the patterns of nature and creating new tools with which to express ourselves.

I have to wonder if some expectations around tools and media might be tied to the content. To be specific, do some art appreciators expect traditional methods for a time-honored subject like landscapes? If so, I wonder why?

I also wonder how “traditional” the subject of landscape really is? Landscapes are perhaps among the most timeless subjects of all (at least until, or if, humans leave earth, in which case landscapes will mean something else entirely). At the same time, landscapes are also among the most changeable and dynamic of subjects. We live in a time of great upheaval in terms of our cultural relationship to the land, and the entire biosphere for that matter. That aside, using new tools and seeking new interpretations of a subject so closely tied to humanity strikes me as contemporary.

Since the first time a sharp stone was used to etch a shell, humans have quickly conscripted new technology to create art. Even the tools most artists use today for traditional techniques are products of high technology – advanced pigments, binders, solvents, finish compounds, canvas manufacturing, synthetic brushes, the list goes on. None of these modern materials were available even to classical artists, nor to the impressionists and “modern” artists (a concept itself which is now over a century old). While some artists work to preserve traditions in cultures across the globe, it makes sense that most artists create using the tools of the times.

And that’s true across all kinds of art forms. Sculptors, for example, are quick to grab hold of any new industrial technology to make statements at the largest and smallest scales. Musicians push the limits of digital tools daily as each generation defines a new sound. Armies of visual artists work in the gaming and movie industries, bringing art to life in ways humans have never experienced.

VR Dragon by Robin Hostick, created using Tilt Brush, is a virtual 3D image - in a VR (virtual reality) environment, you can stand behind it, above it, or inside its mouth!

Working in the design field as a landscape architect, I basically grew into the information age along with technology. My earliest jobs involved hand drafting on paper, actual “blueprint” reproductions, and illustrations using markers and colored pencil. Today, all drafting, illustration, production and communication is digital. I’ve been playing with all kinds of new technologies as they come out, from the very first version of Adobe PhotoShop to Tilt Brush (this tool enables artists to create in VR, literally to paint in the air around you).

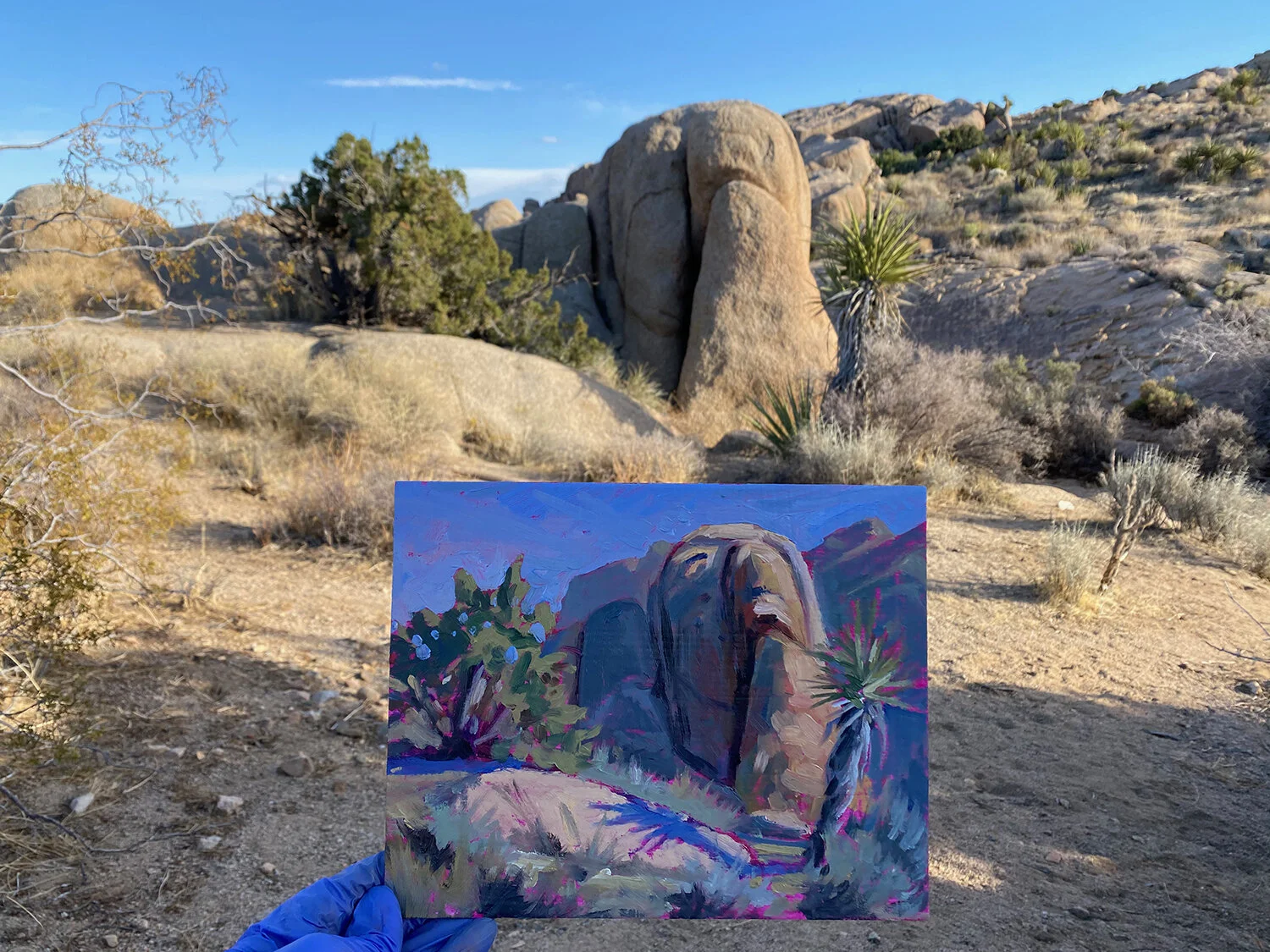

Forward to 2019. I was playing with my latest – and arguably the most powerful and intuitive tool yet – working with a digital image of a painting I’d just finished. At first, I was just pushing the work in a slightly more abstract direction, playing with shapes, color and movement. After a while, it became more like an engrossing meditation, this process of crafting complex curves and intersections of form, each in relationship to the next.

Sixty-five hours later, the piece was finally complete. The image represented the same subject, with colors and composition derived from the original painting, but a new work had emerged. It came alive in a way that was surprising and pleasing.

I pursued the technique through several more works, and by now have logged maybe around 150 hours. I gave the technique a name, “dynamic patternism,” to describe how it works and offer a hint at the result.

While the term “digital art” may sound automated, dynamic patternism is anything but. The latest work is comprised of around 120,000 individual strokes of the stylus, that together create a thousand beautiful shapes (a strange little mantra that goes through my head when I work on these). It’s a little hard to describe in words, so if you’d like to see a demonstration, check out this video (https://youtu.be/hqbQbE84uSs).

My goal with this technique is to imbue the works with movement, and to awaken within the viewer something of the sense of joy and wonder I feel in the presence of natural beauty. For me, the experience of nature is always moving, changing, blending from one moment to the next. This technique, maybe partly as a result of its precision and allegiance to the perfection of abstract forms, seems to convey that wonderful sense of “aliveness” in the landscape.

I sometimes think of it as a metaphor for the seamless interconnection of systems and species, the fluid interaction and exchange of energy between all things. If ever I heard a fitting description of the natural world, that would be it.